Before the economic storm severely hit Venezuelans wallets, crime was people’s biggest national concern, topping scarcity, inequality, inflation or anything. In spite of being bumped, it is still is a huge concern. But … what can we do about it? As it turns out, sometimes the answer involves just a little bit of ingenuity, and a lot of guts.

Before the economic storm severely hit Venezuelans wallets, crime was people’s biggest national concern, topping scarcity, inequality, inflation or anything. In spite of being bumped, it is still is a huge concern. But … what can we do about it? As it turns out, sometimes the answer involves just a little bit of ingenuity, and a lot of guts.

The background

In 1989 Venezuela’s homicide rate was 13 per every hundred thousand persons. By 2012 that number had increased four-fold, reaching 54 per every hundred thousand, and 79 by 2013. This was confirmed by the Venezuelan Government official statistics, and also by the UNODC’s 2013 global study on homicide (the 2013 numbers are claimed by the Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia, although we have our issues with those figures).

The World Health Organization says that a country faces an epidemic of violence when the homicide rate exceeds 10 murders per every hundred thousand persons. According to this, Venezuela has been suffering from an epidemic ever since the not-so-roaring 1990s, crippling the state’s capacity to cope with crime. To add some perspective to this dreadful plight, only two out of 145 countries since 1995 (El Salvador and Honduras) have topped Venezuela’s homicide rate. As a matter of fact thanks to Honduras staggering violence, Venezuela is not yet labelled as the most violent place on Earth. It is, by far, the most violent “large” country in the world.

At a time when both the developing and developed world in general have neutralized a surge in violence, Venezuela’s Government has designed, implemented and scratched 20 security plans over the last 15 years in the efforts contain violence in the oil-rich nation. All of them have failed. This lack of continuity in public policy (among other things) has been a key determinant for explaining the crumbling state of affairs in the streets.

The Sucre experience

As the economic crisis depletes the state’s coffers, less money is allotted towards fighting crime. UNder these circumstances, how is it possible to at least ameliorate the rampant crime wave in Venezuela?

This question was assessed and tackled by Sucre municipality in eastern Caracas. Sucre has around 1,2 million inhabitants dwelling in its territory (although INE says it is half that number), ranging from a few spaces of middle-class neighbourhoods to a vast dominion of shantytowns, reflecting Sucre’s overwhelming poor-majority barrio populace. From 2000 till 2004, Sucre had about 500 homicides per year, or roughly 49 homicides per every hundred thousand persons. Ranging from 2005 till 2008 (the previous mayor’s last tenure in office) it had risen to 562 homicides per year, and an average of 54 homicides per every hundred thousand persons.

In 2009, the arrival of a new administration led by mayor Carlos Ocariz, a prominent figure of the Primero Justicia opposition party, security was made a key priority. Ocariz though Sucre could promote the idea that violence could be contained just as Medellin in Colombia. In 2008, 722 homicides took place within Sucre’s territory, and by 2013 the number had decreased to 498.

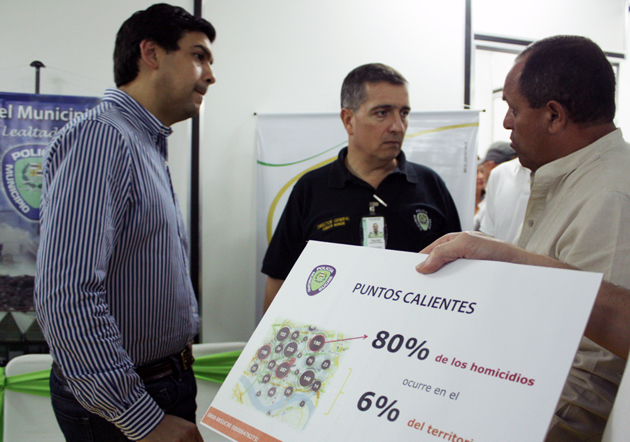

The main drivers behind this decline were improving Sucre’s police department (one of the biggest in the country), and bolstering social policies aimed specially at the youth. But these things cost money, and Sucre’s cash-strapped budget needed some rethinking. So in the midst of 2013, in partnership with researchers from CAF and friend of the blog Dorothy Kronick, Sucre launched a pilot program called “Puntos Calientes” (Hotspots), one I had the priviledge of participating in when I was working as a public policy analyst in Sucre.

Puntos Calientes was designed to pinpoint the concentration of violence in Sucre at a microlevel, evaluate the administration’s public policy impact in such microplaces, and minimize the incidence of violence through effective and intelligent patrolling in those areas. The study concluded that 80% of the violence in Sucre (homicides, wounded from arms) was concentrated in just 6% of its territory. So by highlighting the street corners, the little alleys and stairs where most of the action was taking place, Sucre’s policemen (Polisucre) were better equipped when engaging against criminals in their patrolling routes. Sucre also intervened in those places by promoting cultural activities such as movie nights to take control of those crime-ridden places away from gangs.

After the first three months of implementing this pilot program, we observed a 26% drop in violence vis-a-vis the same period a year before, showing good signs of a possible expansion of this public policy.

Still, results were premature, although Sucre is considering expanding the program in middle class neighbourhoods as you’re reading this. But even if it’s doomed to fail for whatever reason, or even if correlation doesn’t translate into causality for grading Puntos Calientes with an “A”, Sucre deserves some credit for thinking outside of the box.

Last but certainly not least I leave a video made by CAF and the Sucre mayor’s office explaining more thoroughly what’s this plan all about.

This approach has been tried in many places, and has usually worked. In fact, early on in the Chávez administration, Caracas mayor Alfredo Peña brought former NYPD chief William Bratton to Caracas to help implement such a thing. Funding dried up, and the efforts were quickly abandoned once the government went to war against Peña, and the opposition at large.

Sucre’s effective implementation of this program is a sign that you don’t need huge sums to fight crime. All it takes is a little brain power to use the funds you have where they are needed the most.

“All it takes is a little brain power to use the funds you have where they are needed the most.”

This approach could solve most, if not all Venezuelan problems. The thing is Chavizmo doesn’t even know where funds are needed most, or else considers “preserving the ruling party” a priority above and beyond all others.

I suspect it’s the latter.

LikeLike

Great article Carlos!, Just to complement it a bit, I post a super important link =)

http://www.localis.la/patrullaje-basado-en-puntos-calientes/

LikeLike

What a refreshing change! It gives my joy to read something good about Venezuela.

LikeLike

Another area in which results can be achieved relatively cheaply: domestic homicide.

While situations no doubt differ in different countries, domestic murders often occur because the parties are involved in more and more serious abuse, culminating in death.

Separating the parties early on can lessen the pressure which otherwise builds up. Domestic homicide in Canada was cut by half using this method.

LikeLike

Seeing the “Puntos Calientes” photo reminded me of the “hot spots” method used in driving down crime in NYC and in other US cities. I was all set to write a comment about that, but further reading down showed me you already had it covered.

It definitely worked in NYC. NYC had previously earned the reputation of being Crime City, but these days the crime and murder rates are close to the national average, with crime and murder rates much lower than most big cities in the US.

Where there is a will, there is a way. It would appear that Chavismo doesn’t have much of a will, as crime distracts the populace from focusing on such things as tyranny, incompetence, and corruption from the GOV. Also note this crime reduction effort is coming from a municipality which voted in oppo officials, not from a Chavista municipality. But I am merely stating the obvious.

LikeLike

Exactly. As a matter of fact this methodology for coping with crime has been undertaken in many US cities but not for figuring out homicides or arms-related crimes. It was focused on other crimes such as robberies that tend to have a higher frequency of occurrence than homicides. The purpose was to adopt this approach for analyzing homicides among other traits of violence in order to boost Polisucre’s capability in patrolling routes and Sucre’s intervention through cultural and recreational endeavors.

The main issue with Chavismo is that it has undermined or blighted any Rule of Law that was left in this country, and as a consequence crime and violence has been booming.

LikeLike

“It definitely worked in NYC. NYC had previously earned the reputation of being Crime City, but these days the crime and murder rates are close to the national average, with crime and murder rates much lower than most big cities in the US. ”

While it certainly worked, it’s unclear how much of the drop in crime was directly related to the adoption of COMPSTAT (and similar programs). Crime declined significantly all across the USA since it’s peak in the early 90s, and that includes places that didn’t adopt this type of policing approach. Social scientists differ on to what extent different factors accounted for this nationwide drop.

LikeLike

“Sucre has around 1,2 million inhabitants dwelling in its territory (although INE says it is half that number)”

!?

INE (census 2011): 600,351 inhabitants (http://www.ine.gov.ve)

INE (census 2001): 546,766 inhabitants

How could you have a clear policy planning if there is a so high discrepancy about basics demographics facts? Are you counting as ‘inhabitants’ people working in Sucre but living outside (it could make sens for mayor’s office)? Are they counting for homicide rate?

How can we compute homicides rate if denominator is not well defined?

“Ranging from 2005 till 2008 (the previous mayor’s last tenure in office) it had risen to 562 homicides per year, and an average of 54 homicides per every hundred thousand persons.”

500 murders/600,315 = 83,3 homicides per every hundred thousand persons.

562/1,200,000 = 46,8

How do you obtain a rate of 54?

LikeLike

Indeed. This has been a major setback for designing any public policy in Venezuela, and not just in security-related policies. By our account (at least when I was at Sucre) INE claimed that there were around 600 thousands people living in the Municipality. Yet by our estimates of the amount of garbage that Sucre generated in 2010 the figure surpassed the million people threshold exceedingly. Also given the large number of “barrios” in Sucre and how concentrated they are the evidence points towards an over million people figure than a mere 600k persons.

Just to conclude, INE is in my humble opinion a big sham in regards to official statistics. According to INE only 20% of Miranda’s households are considered to be in state of poverty (they don’t even set a poverty line or income for classifying whether you’re poor or not, they just simply asked people if they considered themselves living in poverty or not)…Solid data-gathering.

Ooh, and if Sucre’s population really was around the 600k figure, the homicides rate would almost top Honduras 90 homicides per every 100k persons, again contradicting the Revolution’s own official statistics.

LikeLike

Having higher amount of garbage than estimated only by permanent population is normal, because there is a lot of internal movility of persons each day, and probably some areas of sucre are net receivers (at least people coming from/going to Guarenas/Guatire by bus spent one hour in Sucre each day). As order of magnitude, Paris (2,34 m inhabitants, have a estimated net daily entry of 700 thousand people coming from suburbs, plus tourists).

Even if INE is doing a terrible work, we are talking about a 2-fold error. Comparing 2011 results with 2001 census, we have almost 1% of population growth per year, that is reasonnable rate. Unless you can show that INE was performing the same huge systematical errors in 2001 and 2011 (or even before, the historical data is consistent), my bet is that the INE’s estimations are more accurate than perception coming from garbage tons or perceived density.

Concerning homicide rates, I am not specialist, by I guess it is difficult (and maybe useless) to calculate this rate for a limited geographical area, if you don’t have a precise picture of human daily flows and how much people is actually somewhere when murders are happening.

LikeLike

We don’t have “issues” with the Observatorio de Violencia’s numbers. Their numbers are as close to meaningless as they could possibly get. I find it embarassing that guys who basically make a linear extrapolation to predict crime get to call themselves “academicos”…

LikeLike

Now, rant aside

Carlos, How is this “puntos calientes” approach different from, say, the “cuadrantes” the MIJ is implementing? The idea seems to be simply that police patroling should increase in places where crime is more common.

LikeLike

the “cuadrantes” quadrants as far as I know are no longer in place or haven’t been in a while (I’ll have to dig deeper into this). The idea of the “cuadrantes” comes from Colombia’s Police Department in which a couple of policemen were responsible for patrolling a determined area or quadrant. This was done in Bogota some years ago. In Venezuela what MIJ tried to do was to forged a coordinated effort with different types of units (Municipal policemen, National guards, PNB) to reduce crime or at least mitigate it. The quadrants were set by MIJ and shared with Polisucre for example.

Puntos calientes on the other hand was designed by Sucre to map out where the action was taking place at a microlevel (not sectors of a neighbourhood or barrios but rather on small alleys, stairs, corners etc). With this information, Polisucre’s patrolling endeavors were prioritized (subject to the number of available officers and vehicles) into these microplaces. But Polisucre patrolled these areas for just 30 minutes a day (two turns of 15minutes each) randomly so as to be ahead of criminals and induce a higher cost on them if they were to engage in a criminal activity.

Regarding your rant towards the OVV, of course is not appropiate to extrapolate a linear explanation for estimating the homicide stats. The problem is that without sufficient data which has become hugely on dearth as basic groceries are, policy makers and public policy wonks are finding it very hard (if not impossible) to come out with some numbers that may reflect what’s been going on in the country, and that often yields diverting conclusions.

LikeLike

In math that’s Pareto distribution or pareto analysis. It was widely used in what was called TQM (Edward Deming).

LikeLike

“Funding dried up, and the efforts were quickly abandoned once the government went to war against Peña…”

Yet another proof that the crime wave that slaughters thousands of venezuelans each year is a coldly calculated policy of chavismo.

LikeLike

Two questions from the police viewpoint–

1. If its true that police commit a large portion of the murders, then what would happen if hundreds of police are concentrated into one small area? Would the murder rate go up or down? Remember that under Chavismo, police are immune from prosecution.

2. The police become targets in the bad areas. Why would they want to go into these areas?

LikeLike

OT: Eva Golinger at work

http://en.ria.ru/politics/20141001/193532607/Former-Honduras-President-Slams-US-for-Interfering-in-Countrys.html

LikeLike

Heh, nothing as pathetic as a former president calling the waaambulance.

And ZeFuéYa is one of the most pathetic losers out there.

LikeLike

The problem of violence has been effectively addressed in Mexico City, as well as Bogota. The situation in Caracas can be addressed, and it looks from this post like there are people who understand how to address it and where to look for solutions. Here’s a recent update on Mexico City:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/nathanielparishflannery/2013/06/18/political-risk-is-crime-rising-in-mexico-city/

LikeLike